In the chapter on leadership and justice in Mishkat al-Masabih, we find this saying of the Prophet: “As you are, so shall be those appointed to govern you.” (Shuabul Iman, Hadith No. 7006)

From this tradition, we learn about two things: first, the issue of the individual human condition in terms of thought, attitude and behaviour; and second, the issue of organisation of collective human affairs. In other words, political leadership. The above tradition of the Prophet tells us that a given society’s political structure will reflect or shape the condition of the people of that society.

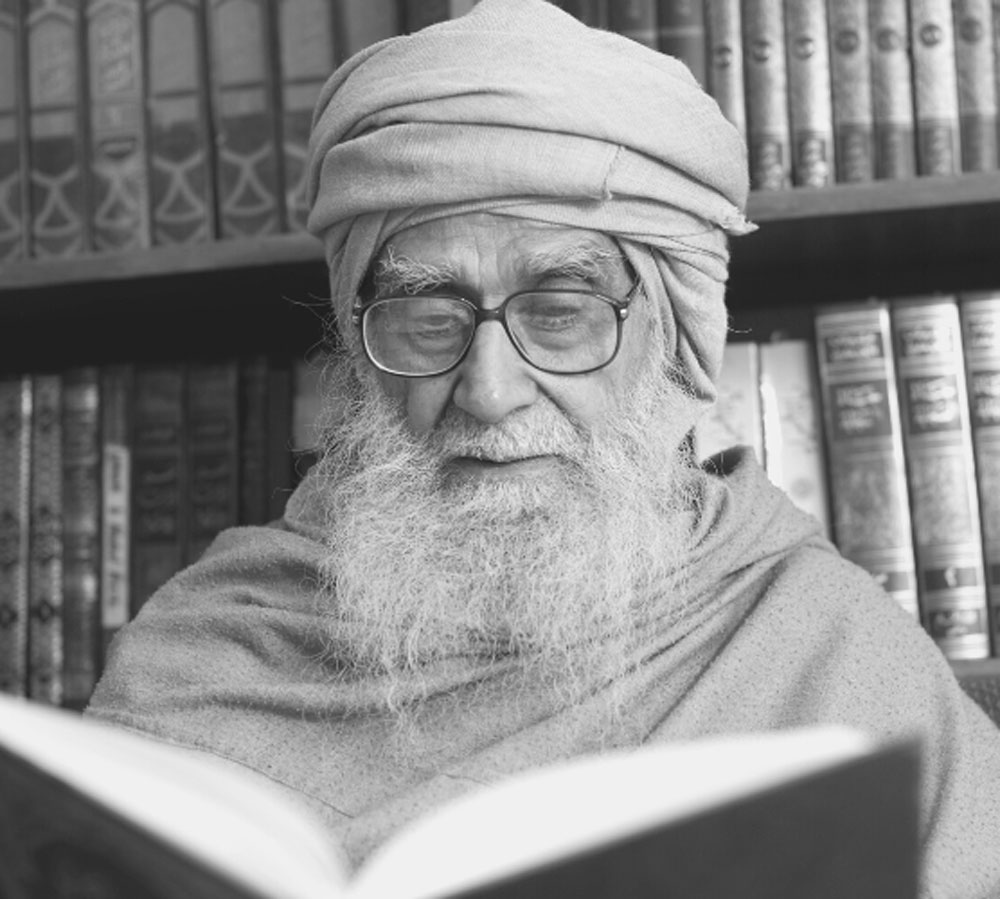

The Ulama are eternal guardians of people’s way of thinking. Their task is to set right the mindset of people in every age, guiding them on to the right path while leaving the task of governance to the politicians.

A healthy society must observe this distinction of roles, tasks and responsibilities. Ignoring this distinction is bound to lead to severe disruption. People need proper guidance to develop the right mindset because the proper system of government results from the right human mindset. Conversely, if people’s mindset is corrupt or debased, the system of government will follow suit. This division of work resulted in a glorious history of scholarship and dawah work, which is the most precious legacy of the Muslim community.

Had all the people been engaged in jihad and other such defence-related activities, then certainly a vacuum would have been created in Islam, never to be filled again till Doomsday.

In the two generations that followed the Companions of the Prophet, this division of spheres of activity was maintained. People were engaged in various fields of knowledge, and there came to be the Quran reciters, Hadith scholars (muhaddithin), fuqaha (jurists), Ulama, dayees (those who conveyed God’s message to people) and Sufis. All of them focused on their respective spheres of activity. This pattern continued for around a thousand years.

This guidance received at the very beginning of Islam set the course of future activities of the Muslim community. During the first phase, one group of the Prophet’s Companions engaged in activities such as defence. While the other group, for instance, Abdullah ibn Masud Abdullah ibn Umar, devoted themselves to academic and dawah (conveying God’s message to people) fields.

In life, people’s mental fabric in terms of thought, attitude and behaviour is far more important than societal or political leadership. The former’s position is of base or foundation, while the latter’s is of superstructure resting on this base. Those who judge by appearance often mistakenly perceive this upper structure as more important than the base. In reality, however, the base is much more important. That is why the position or status of the religious leaders is loftier than that of the political leaders.

Consequences of Breaching This Precedent

The tradition of maintaining a clear distinction between the spheres of activity of the Ulama and the political class was first breached in India in a significant way at the time of the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb (1618-1707). Although Aurangzeb was born in a royal family, he was a religious scholar in the complete sense. His circumstances led him to become a religious scholar rather than an emperor. However, he did not accept this role. In 1658, his father was dethroned and imprisoned in the Agra Fort. Subsequently, in 1659, he killed his elder brother, Dara Shikoh. Afterwards, he ruled for about half a century as the head of the Mughal Empire.

Even without possessing the “throne”, Aurangzeb had great resources at his disposal. Had he played the role of a religious scholar instead of an emperor, he could have effectively carried out this task of laying the foundation and become a model for the Islamic scholars to emulate for several centuries.

The foundations of modern science were being laid in Europe during Aurangzeb’s reign. The impact of this had reached India’s shores by Aurangzeb’s time. However, he remained blissfully unaware of this development. Instead, he remained engrossed in his political quest of a temporary nature. His father, emperor Shah Jahan, had built the enormous mausoleum, Taj Mahal. Aurangzeb had every opportunity to build a ‘palace’ of knowledge. By letting Dara Shikoh handle the governance of the Empire, he could have focused on establishing an ‘educational empire’ in India. Had he devoted himself to this task, he would have benefitted Islam and the Muslims much more than what he unsuccessfully tried to do through politics and war.

Had Aurangzeb travelled to Europe, instead of spending years fighting wars in the Deccan, he would have realised that what he was doing was totally against the demands of his times. He sought to establish, to his way of thinking, the supremacy of Islam through the ‘politics of the sword’. He was unaware of the new age which had already dawned—and which would soon arrive in India, too—when the ‘politics of knowledge’ would become a powerful means of establishing the dominance of a community.

It appears that Aurangzeb and other Ulama of his age were probably unaware of not only the intellectual and scientific developments that were taking place in Europe at that time, but strangely enough, they were also unaware of the progress that the Muslims had made in this regard during their rule in Spain from the early 8th to the late 15th century.

When the Muslim rule collapsed in Spain, many Spanish Muslim scholars and scientists left for other lands. At that time, an influential Muslim Caliphate (1300-1924) ruled over Turkey. Some Muslim scientists, fleeing Spain, headed for Turkey, but they received no support in the royal court. Not long after the dissolution of Muslim power in Spain, the Mughals established their empire in India in 1526. However, the powerful Mughal Emperors never invited some great Spanish Muslim scientists to India to carry on their scientific work, which had come to a standstill in Spain. Such academic work based on research and investigation required governmental patronage. That is why, when the scientists of erstwhile Muslim Spain failed to find opportunities in the Muslim world, they shifted to Western Europe instead, where they received the patronage of the non-Muslim rulers. This is why the work in science that had begun in Muslim Spain reached its climax in Europe rather than in the Muslim world.

Because of his unawareness of all these developments and his inordinate interest in politics, Aurangzeb failed to take any action in this regard. Hence, modern science reached its culmination in Europe, and the entire credit for the progress and development of modern science went to Europe.

The conditions that gave rise to the ‘modern age’ and the earliest manifestations of this new age had already appeared when Aurangzeb ascended the Mughal throne. The first model of the spring-driven watch, which was to replace the old-fashioned clock, was produced in Germany in 1500. Vasco Da Gama of Portugal landed on the Malabar Coast in southern India in 1499, inaugurating a sea route that connected Europe with Asia based on advances in geography and naval technology. In 1501, Portugal had captured Goa. A century later (in 1600), the British East India Company was set up, and a short while after, the French East India Company was founded in 1664. However, because of his political involvements, Aurangzeb was unaware of these developments or did not give them the importance they deserved, although they suggested the grave external challenges they would soon pose, not just to India but the entire Muslim world.

Long before Aurangzeb was born, in the 2nd century C.E., a rudimentary form of printing had been invented in China, which was later further refined by Willem J. Blaeu in 1620 in Amsterdam and came to be known as the Dutch Press. The first all-metal press was constructed in England in about 1795. Some hail Aurangzeb for making copies of the Quran in his hand. Strangely enough, he seems to be unaware that in 1455, Gutenberg had printed the first copy of the Bible in the printing press invented by him, thereby taking the Christian missionary enterprise from the age of handicrafts to that of the machine. Had Aurangzeb known of this development, he could have set up printing press in India rather than engaging himself in making copies of the Quran by hand.

Cambridge University was established in 1571, while the University of Paris and the University of Oxford were established much before that—in the 12th century. Aurangzeb reigned in the 17th century. How much better it would have been had he focused on a much more important task—that of establishing a major university in India for all the various branches of knowledge! He could have set up centres to research in various contemporary disciplines. He could have established a centre in Delhi to translate essential works by European scholars. He could have formed an academy of religious scholars who could have acquired knowledge of modern subjects and engaged in research on them. However, he failed to engage in any such endeavour. Moreover, the simple reason for this was that he did not agree to observe the distinction in the spheres of activity mentioned above, that is, between the religious leaders, on the one hand, and the political leaders, on the other.