Mushtaq Ul Haq Ahmad Sikander, New Age Islam

A Stark Meditation On Death As Life's True Compass, A Lucid Da'Wah Text That Turns Our Fear Of Mortality Into A Rigorous Rethinking Of Purpose, Character, Happiness, And The Hereafter.

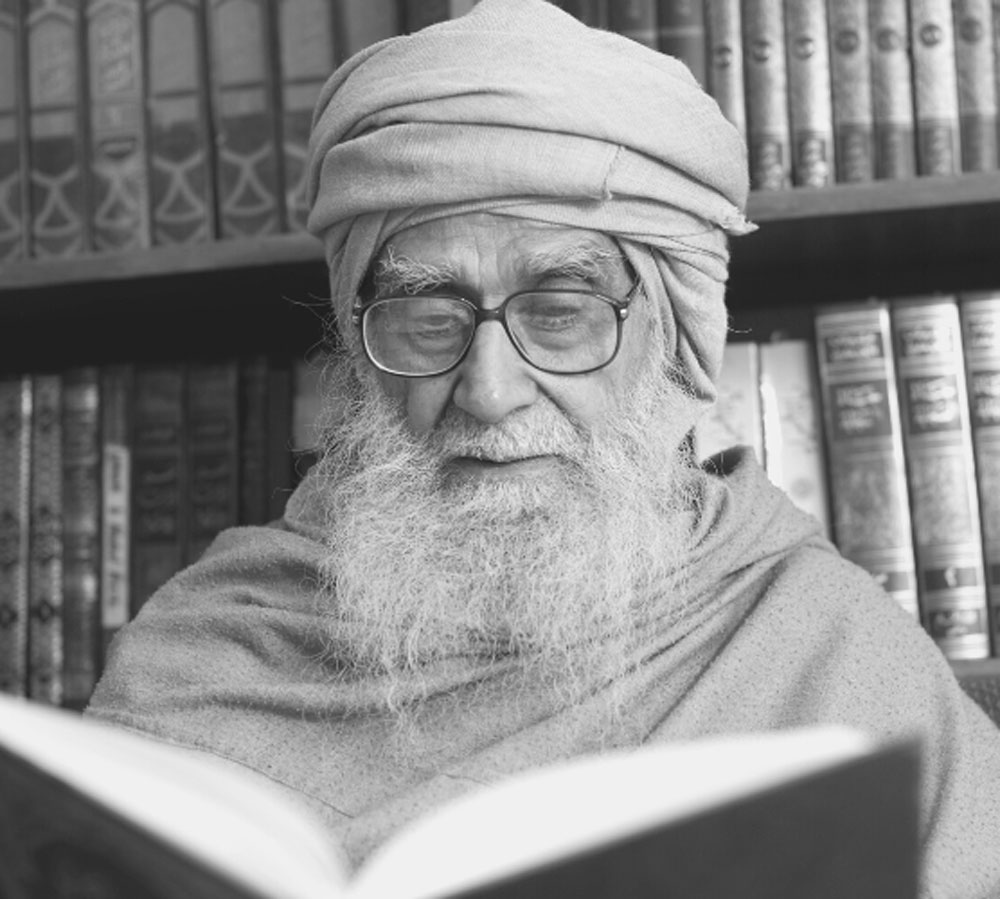

Maulana Wahiduddin Khan’s “Safar-e-Hayat” is, on the surface, a small book about a single, uncomfortable subject: death. Yet from its opening pages it is clear that the late veteran Indian Islamic scholar is attempting something larger and more ambitious. It is a compact manifesto on why we exist, why we must die, and how a clear-eyed engagement with death can fundamentally reorder how we live.

Written in simple, unadorned Urdu, “Safar-e-Hayat” reads less like abstract theology and more like a long, sober conversation with an elder who has spent a lifetime thinking about the end of life. Its journalistic power lies in the way Maulana Wahiduddin Khan persistently drags an issue we habitually repress—our mortality—into the harsh light of day, and then insists we not look away.

A book about death that is really about life

From the very introduction, Khan frames the project clearly: this is Dawah, not in the narrow sense of polemical preaching, but as an invitation to think—seriously, urgently—about one’s purpose. For him, Dawah begins with self-questioning: Who am I? Why was I created? What happens after I die?

The central claim of the book is both stark and uncompromising: human beings have been placed on earth to be tested, and everything they have—intellect, freedom, opportunity, even time—is on loan from God. This world, he repeatedly reminds the reader, is not home but a “selection ground” where people qualify themselves, by their choices, for either heaven or hell. It is a nursery for the hereafter, not a final destination.

Khan’s prose constantly pushes the reader away from the comfort of vague spirituality and towards the discomfort of consequences. If the human condition is an exam, then death is not a random biological accident; it is the moment when the paper is taken away and the answer script is submitted. What matters, then, is not whether one “believes” in some abstract sense, but how one uses the test: what one does with the powers that have been “bestowed”—a word Khan uses deliberately—to emphasize that nothing is self-made.

Death as the great un-ignored reality

One of the book’s most arresting features is its blunt diagnosis of how modern humans deal with death. We are, Khan suggests, profoundly lackadaisical about the only event that is absolutely guaranteed. He attributes this not to reason, but to conditioning. Society trains us to focus on careers, families, consumption, “success”—almost anything, in fact, except the inevitability that all of this will come crashing down.

Old age, in his analysis, is nature’s mercy and warning, a visible symbol that the exit door is near. Wrinkled skin, weakening limbs, diminishing social relevance—these are not merely biological decay; they are reminders that the curtain is about to fall. Yet even this gentlest of wake-up calls is routinely ignored. People behave as if old age were a problem to be cosmetically masked, technologically managed, or medically postponed, not a signal to prepare for departure.

But, Khan adds, not everyone is granted such advance notice. Death can, and often does, arrive as a surprise. That unpredictability is built into the system to keep humans in a state of readiness. If the exam were scheduled, everyone would cram at the last minute. The fact that we do not know our personal deadline is part of the moral architecture of creation.

The loneliness and compulsion of dying

Khan’s language sharpens when he describes what he calls the “lonely affair” of death. No one, he reminds us, can accompany us beyond the grave. Family members, friends, admirers, rivals—all remain on this side of the door. The journey into the next life is solitary in the most radical sense; all relationships, all social identities, are stripped away at the threshold.

He also calls death a “compulsory expulsion.” The phrase carries a jolt. If life on earth is a temporary stay in a training camp or examination hall, then death is the invigilator’s command to leave. Whether you feel ready or not, whether you are “enjoying” the paper or still struggling with question one, no extensions are granted. The expulsion is mandatory.

Yet, and this is crucial for Khan, this forced nature of departure does not mean we must go unconsciously. He repeatedly contrasts the heedless dying of “others”—those who never consciously prepared for the encounter—with the deliberate, wakeful embrace of death that the believer should cultivate. To die consciously, in his vocabulary, is to meet one’s Lord with awareness, acceptance, and spiritual readiness, rather than in a state of denial or shock.

Death as a killer of dreams—and a creator of urgency

One of the strongest and most journalistically vivid threads in “Safar-e-Hayat” is Khan’s critique of worldly ambition. The death of any individual, he writes, annihilates not only their body but their desires, their carefully constructed claims to fame and greatness, their brands, reputations, and narratives. The ambitions that once animated them—professional, political, romantic, intellectual—are extinguished with brutal finality.

In a phrase that crystallizes this idea, he calls death a “killer of dreams.” The observation is more than rhetorical. Khan wants the reader to feel the acute mismatch between our long-term plans and our short-term lease on life. Skyscrapers, institutions, movements, even civilizations are subject to the same erasure. The book repeatedly punctures the illusion of permanence on which contemporary life rests.

Yet this is not meant to induce despair. For Khan, the awareness that everything worldly will be annihilated is precisely what can awaken an “intellectual quest.” When a person truly grasps that their desires will be cut off mid-sentence, urgency is born. Time, once seen as a limitless backdrop, suddenly appears as a finite resource, tightly rationed. The reader is pushed to ask more serious questions: If the dream ends abruptly, what is worth chasing? Who am I beyond my projects and possessions?

In this sense, death does double work in the book. It destroys illusions, but also clears space for more enduring concerns to arise.

DNA, nature, and the hidden curriculum of death

A striking argument Khan advances is that our genetic makeup does not, on its own, carry an explicit “program” for understanding death. In our DNA, he claims, there is nothing that directly tells us what death is or what lies beyond it. God has, in his view, intentionally withheld this information from our biological code so that humans may discover, ponder, and consciously work towards it.

This idea provides a bridge between revelation and human reflection. For Khan, the absence of a built-in death-awareness mechanism is not a flaw; it is an invitation. The universe hints constantly at mortality—in decay, in cycles of growth and death, in the fragility of life—but does not spell it out in purely biological terms. The missing piece is supplied by divine guidance, which informs us that death is not the end, but the initiation of a new life.

The tragedy, he laments, is that most people are unaware of this—or live as if they were. The after-death reality, in his telling, is like a vast, imminent event for which almost no one is preparing. We plan weddings, careers, retirements, vacations. But the one transition that is absolutely non-negotiable is left unplanned, treated as an abstraction rather than an approaching certainty.

From here, Khan makes a broader civilizational critique. Modern civilization has achieved staggering technological feats, yet has failed at something as basic as creating a truly “pollution-free industry.” Nature, in contrast, constantly recycles, purifies, and balances through intricately designed, non-polluting processes. The implication is clear: if human beings cannot even manufacture in harmony with the environment, their arrogance about explaining life and death without reference to a Creator rings hollow.

Preparing for death: the “heavenly character” in this world

If death is certain and the hereafter real, the pressing question becomes: how does one prepare? Here “Safar-e-Hayat” moves from diagnosis to prescription. Preparation for death, Khan argues, is not about rituals at the end of life; it is about the entire pattern of living. The aim is to cultivate a “heavenly character” in this world—traits that will render one eligible for heaven in the next.

This “heavenly character” is sketched not in systematic theological jargon but in accessible moral language: God-consciousness, humility, gratitude, patience in adversity, restraint in prosperity, and above all, a living remembrance of God. Those who remember God in life, he suggests, will be near Him in heaven. Those who forget Him—losing themselves in the noise of the world—will find themselves distant in the hereafter.

Khan distinguishes between “pre-death thinking” and “post-death thinking.” Pre-death thinking focuses obsessively on immediate gains: reputation, wealth, pleasure, comfort. Post-death thinking asks how any action or habit would look when viewed from the vantage point of the grave. The believer’s task, according to him, is to import post-death thinking into this life, to live now as someone who knows that their every choice will be revisited later.

This world, he repeats, is a nursery. The qualities suitable for the eternal home must be developed here, while time and freedom remain. Heaven is not a random reward but the natural habitat of those who have grown into beings capable of inhabiting it.

Fake happiness and the missing fulfillment

One of the book’s more resonant themes, especially for urban, modern readers, is its discussion of happiness. Khan draws a sharp line between what he calls “fake happiness” and genuine, lasting joy. Fake happiness is produced by consumption and distraction: entertainment, status, sensual pleasure, digital validation. It is immediate, intense, and fleeting, masking rather than addressing the deeper restlessness within.

Real happiness, in his argument, is tied to alignment with one’s purpose and Creator. Because this world is, by design, a temporary testing ground, it cannot satisfy the human longing for permanence, security, and total fulfillment. The sense that something is always missing—even in moments of peak worldly success—is not an accident; it is a clue. It hints that the human being is oriented towards another world where that longing will, finally, be met.

“Safar-e-Hayat” insists that recognizing the counterfeit nature of much of what passes for happiness today is a key step in preparing for death. If one continues to chase the fake, one will never develop the hunger for the real. And without that hunger, the call of the hereafter remains muffled.

Style, audience, and contemporary relevance

Stylistically, this is classic Wahiduddin Khan: short chapters, direct sentences, few rhetorical flourishes, and a relentless focus on the moral point. The prose is intentionally uncluttered, designed to reach a broad audience rather than an academic niche. Those familiar with his previous work will recognize his method: everyday observations, occasionally almost journalistic in their concreteness, used to build a larger metaphysical case.

The book’s strength lies in its clarity and its refusal to compromise on uncomfortable truths. Khan does not dilute the doctrines of accountability, heaven, and hell to suit modern sensibilities. Instead, he attempts to show why these doctrines make existential sense in light of the human condition. His tone is not fire-and-brimstone, but sober and insistent—more like a physician explaining a diagnosis than a preacher delivering a threat.

For some readers, especially those steeped in philosophical or literary traditions of reflection on death, the argument may at times feel repetitive or overly linear. The book does not engage in interfaith comparison, philosophical debate, or psychological nuance about grief and dying. Its horizon is explicitly Qur’anic and Islamic, its purpose avowedly Dawah-oriented. It aims to convince, not to theorize.

Yet this single-mindedness also gives the book its force. In a world where discussions of death are either sanitized, sentimentalized, or relegated to horror fiction, “Safar-e-Hayat” offers a starkly different mode: to think of death as the most serious intellectual and spiritual question of one’s life. In that sense, it sits in conversation not only with Islamic devotional literature, but with global “memento mori” traditions that urge humans to keep death constantly in view as a way of clarifying how to live.

Why “Safar-e-Hayat” matters now

Published in 2018 by Goodword Books in Noida, the 208-page volume appeared in a pre-pandemic world, but its themes have only grown more urgent. In the years since, death has moved from being a distant abstraction to a daily headline. Yet even in the midst of mass loss, much of public discourse has focused on numbers, healthcare, and policy, not on the existential question of what death means.

“Safar-e-Hayat” refuses that evasion. It insists that the only adequate response to the ubiquity of death is not just better systems, but better selves. It calls on readers to see their lives as an entrusted exam, their deaths as a compulsory expulsion, and their character as the only luggage they will carry into the next world.

For those already inclined towards religious belief, the book will likely deepen and sharpen their perspective, nudging them away from vague piety towards concrete preparation. For skeptics or the religiously distant, it may function as a provocative challenge: if death is certain, can it really be wise to live as if it were not?

In the end, “Safar-e-Hayat” does not offer comfort so much as clarity. It tells you that you will die, that you will die alone, that you will be answerable, and that the real journey begins after your heartbeat stops. It strips away the illusions of fake happiness and invites you to cultivate a heavenly character while you still can.

Whether one accepts its theological premises or not, the book performs a rare and necessary service: it makes the reader look steadily at the inevitable and asks, again and again, the question that modern life most relentlessly postpones—are you prepared?