Following the modern industrial revolution and the subsequent colonial era, Western nations rose to political and cultural dominance on a global scale. This presented a significant challenge for Muslims. Across the Muslim world, numerous leaders emerged, united in their belief that “jihad is the only solution” (al-jihad huwa al-hall al-wahid). However, despite nearly two centuries of extraordinary efforts and sacrifices, this approach of armed jihad failed to yield positive results for Muslims.

When this issue is analyzed in light of the Quran and Hadith, it becomes clear that the true solution lies in peaceful dawah (invitation to Islam). The Quran instructs the Prophet in such circumstances to convey the teachings revealed to him, with the assurance of divine protection: “And God will protect you from the people” (5:67). Furthermore, the Quran emphasizes calling people to God with wisdom and good counsel, highlighting that even adversaries can transform into allies through this approach: “Repel evil with what is better; then you will see that one who was once your enemy has become your dearest friend” (41:34).

It would not be incorrect to say that the Quran, in its silent language, was calling out: “The only solution lies in conveying God’s message to people.” Yet, why did it happen that present-day Muslims failed to find guidance in this clear message of the Quran? Instead of engaging in the peaceful communication of the divine message to people, they became involved in jihad—specifically in the sense of qital (armed combat). Given the prevailing circumstances, it was not difficult to foresee that such extremist actions would result in nothing but further devastation.

Why, then, did contemporary Muslim leaders make the grave error of adopting the un-Quranic notion that “jihad is the only solution”? The answer lies in their abandonment of ijtihad-e-mutlaq (that is, independent reasoning to derive rulings directly from the Quran and Sunnah. Instead, they adopted an imitative mindset, relying solely on the codified jurisprudence (fiqh) compiled centuries earlier.

At the time, the jurisprudential texts were saturated with rulings on jihad and combat. Every major fiqh book contained extensive chapters on jihad but was entirely devoid of rulings or discussions on inviting people to God (dawah). While the Quran explicitly commands dawah, these leaders had neglected the Quran as a source for deriving rulings, relying exclusively on fiqh. Unfortunately, the pages of fiqh offered no guidance on the concept of dawah.

This highlights the immense value of ijtihad and the detrimental consequences of relying solely on codified fiqh for deriving rulings.

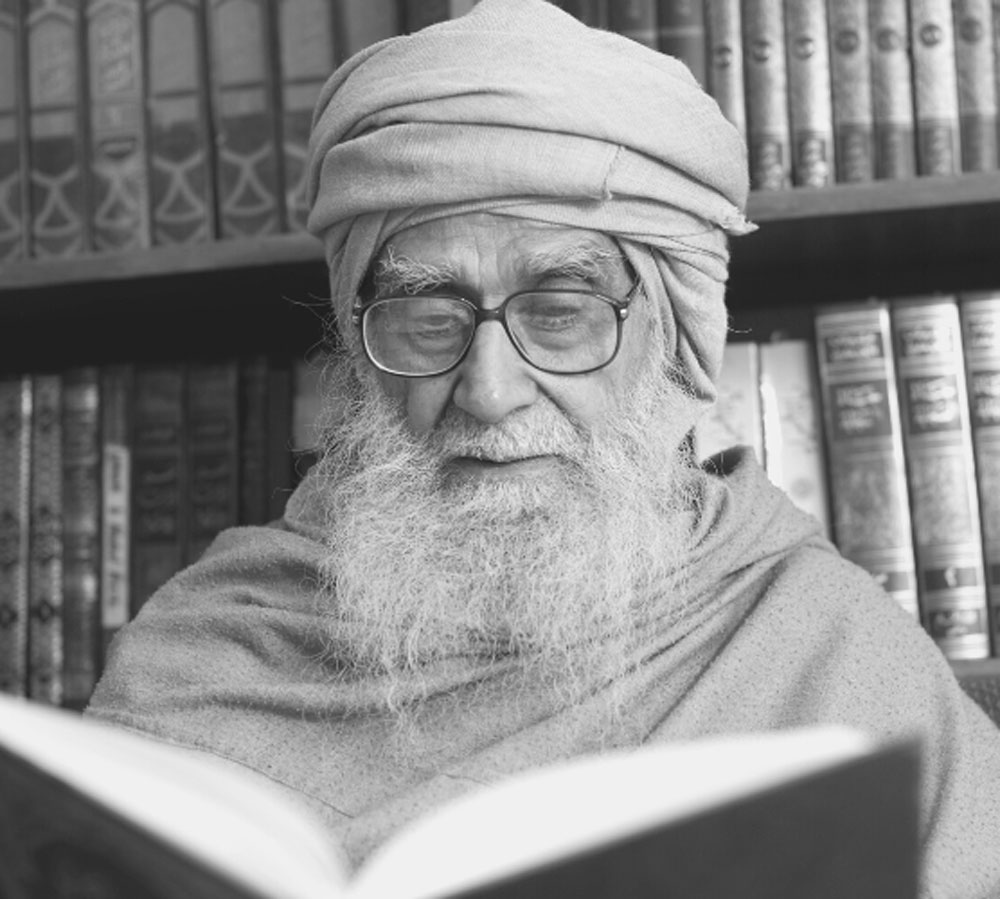

A similar error was made by Muslim leaders of the Indian subcontinent after the rise of British dominance. They declared India as Dar al-Harb (the abode of war). In 1823, Shah Abdul Aziz Dehlvi (1746-1824) issued a fatwa declaring India Dar al-Harb (Fatawa Azizi [Persian], Delhi, 1322 AH, p. 17). Subsequently, 500 ulama signed a collective fatwa obligating jihad against the British. Indian Muslims, considering it their religious duty, waged armed jihad against British rule. Despite a century-long struggle, this jihad proved entirely fruitless.

Had these leaders moved beyond their reliance on fiqh, they would have recognized that contemporary India should have been seen as Dar al-Dawah (the abode of invitation), much like certain regions during the early period of Islam. However, their prohibition of ijtihad and exclusive reliance on codified fiqh left them confined to its limitations. Notably, the existing fiqh texts contain rulings on Dar al-Harb but lack any concept of Dar al-Dawah.