Nation and Nationality

The Quran shows that every prophet addressed his non-believing audience with the words ‘Ya Qawmi’ — meaning ‘O my people’ — as seen in verses 7:61, 67, 79, and 85. This Quranic expression indicates that the nationality of both believers and non-believers is the same. In reality, nationality is not determined by religion but by homeland. Religious affiliation is expressed through the word “Millat” (Quran, 4:125), while “Qaumiyat” (nationality) denotes a connection through homeland (Quran, 11:89). In modern times, homeland is universally recognized as the basis of nationality—this is also the Islamic principle. According to Islam, nationality is rooted in one’s homeland.

From this viewpoint, the Two-Nation Theory is un-Islamic. It promotes the idea among Muslims that they constitute a separate nation. Conversely, the authentic Islamic view urges Muslims to see others as part of their own community. They should be able to say “O my people” to non-Muslims, just as all prophets did. The Quran states:

“Mankind! We have created you from a male and female, and made you into peoples and tribes, so that you might come to know each other. ” (49:13)

In this verse, “peoples” refers to groups formed through geographical or national affiliation, and “tribes” refers to those formed through lineage. According to the Quran, both forms of grouping exist solely for identification and mutual recognition—not to indicate belief or faith.

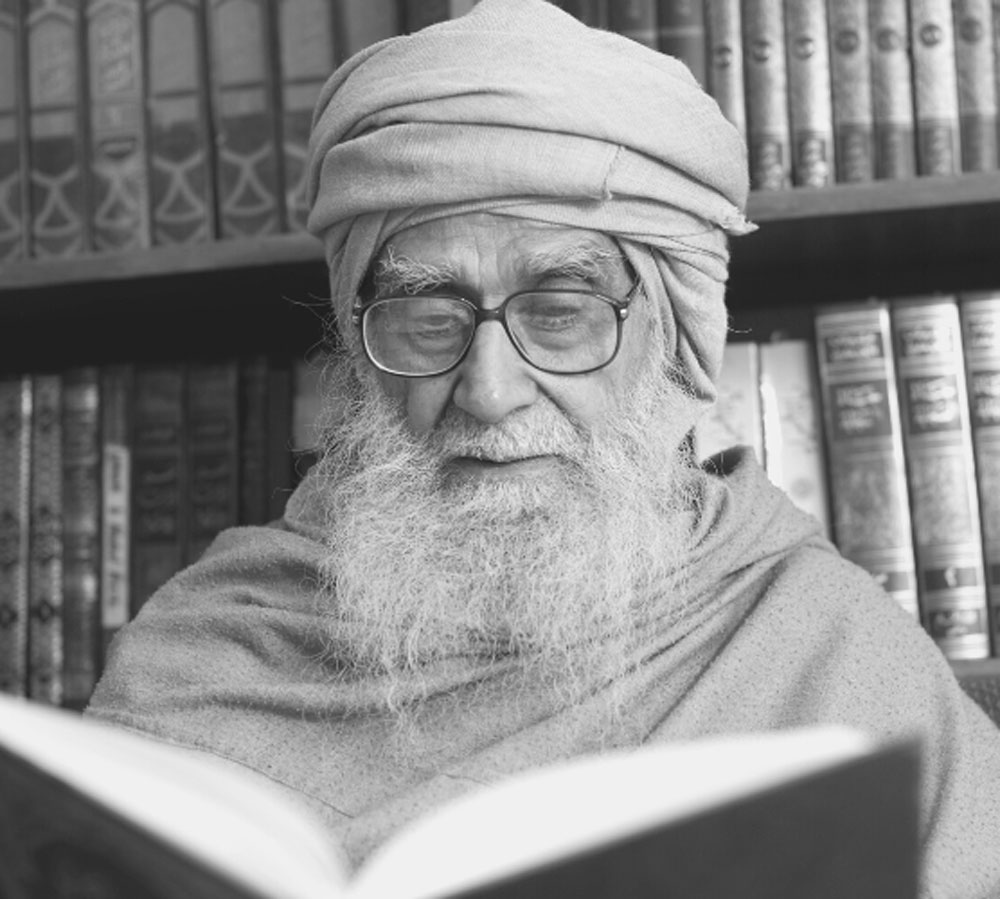

Before 1947, Maulana Husain Ahmad Madani had stated: “In the present age, nations are formed on the basis of homeland.” His statement was essentially correct. However, the phrase “in the present age” was not entirely accurate. As a matter of fact, nations have always been formed on the basis of homeland. What modern times have brought is not a change in this fundamental principle, but rather the use of more structured and formal methods for its identification—such as the inclusion of nationality in passports, the legal definition of nationality in international law, and the codification of citizens’ rights based on their national identity.

It is therefore more accurate to say that the word “nation” is still used today in the same essential sense as in the past. The only difference is that it is now applied with more clarity and precision.

Some interpret nationality in an extreme and ideological way, equating it with religion itself. But this is a form of ideological extremism. Such extremism can also be seen among Muslims. In modern times, some Muslim thinkers have interpreted Islam so narrowly that any system other than Islam is labelled Taghuti (tyrannical or illegitimate). For them, it became forbidden for a Muslim to live under such a system, to seek education, hold government jobs, vote, or refer legal disputes to state courts.

This concept of a Taghuti system was a product of extreme thinking and had no connection to the Islam of God and His Messenger. As a result, the practical demands of life forced even its proponents to abandon it. Today, these individuals have, without formal declaration, effectively distanced themselves from this extremist view.

The same is true of the idea of nationality. Some Western thinkers expanded the concept of nationalism and presented it as akin to a religion. However, when this ideology collided with reality, it collapsed. Today, in practice, the idea of nationality is once again understood and used in the natural, grounded sense in which it was originally used in the Quran.

In the first half of the twentieth century, many Muslim leaders failed to grasp the essential difference between nationalism and patriotism in their natural versus extremist forms. They misunderstood the issue and accepted an unnatural, extreme version of nationalism as the norm—and on this basis, declared it un-Islamic.

A prime example of this is the renowned Muslim poet, Muhammad Iqbal (d. 1938). He, too, accepted the then-prevailing extremist view of nationality and homeland as fundamental, and wrote the following verses in its criticism:

In this age, the wine is different, the cup is different, the cupbearer too is different;

Civilization’s modern sculptors have carved

new idols.

Among these new gods, the greatest is the nation-state;

And the garment it wears is the shroud of religion.

This view of nationality and patriotism is clearly baseless. Strangely, many Muslim scholars and intellectuals of that era treated political developments as existential threats to Islam itself. In reality, no political rise or fall can challenge the enduring nature of Islam.

For instance, when the Ottoman Empire collapsed in the early twentieth century, the scholar Shibli Nomani wrote:

The fall of the Ottoman state is the fall of the Shariah and the Muslim nation—

How long can one remain devoted only to family and home?

This belief—that the downfall of a government equates to the collapse of Islamic law and the Muslim community—is undoubtedly unfounded. Such a thing has never happened in the past, nor can it ever happen. For example, the rightly guided caliphate came to an end, yet Islam endured. The Umayyad dynasty fell, but Islam continued. The Abbasid Empire collapsed, Muslim rule in Andalusia ended, the Fatimid rule in Egypt disappeared, and the Mughal Empire in India disintegrated—yet none of these political declines led to the downfall of Islam.

The same applies to various extremist ideologies that arose in the twentieth century—such as Communism, Nazism, Nationalism, and exaggerated forms of Patriotism. All of them eventually faced the same fate: nature’s law rejected their extreme elements. Ultimately, only what aligns with the natural order endures.

What remained in the end was only what aligned with the natural order.

The eternal law of nature stands above everything else. It automatically eliminates imbalanced and extreme ideologies from the course of history and gives space only to those ideas that are moderate and in harmony with the natural design. (Al-Risala, February 2004)